Makassar’s Spice Monopoly: A Reanalysis of Seventeenth-Century Trade

From Makassar’s spice routes to Silicon Valley’s data flows, the Reboot reassesses this pivot in global commerce.

Our first post at Reboot takes us east — to Makassar, on the Indonesian archipelago. In the 17th century, Makassar thrived as a bustling port city at the heart of the spice trade. Its docks pulsed with a vibrant network of European interlopers, sultanate kingdoms, and Sama mariners whose voyages reached as far as the Australian coast.

Makassar’s rise as a political and maritime power — sustained by emerging technologies of navigation and trade — eventually collided with the Dutch East India Company. By century’s end, the VOC had claimed a monopoly over the region’s lucrative spice trade. Though Makassar proved a financial disappointment for directors back in the Netherlands, a new community of traders, fishermen, and sailors took root, carving livelihoods from the surrounding seas. Scholars note that as global trade shifted toward smaller cargo and a tighter monopoly, Makassar was left behind modern development.

From Spices to Search Engines

Fast forward to the present: Google has been fined €2.42 billion by the European Commission — a regulatory action reminiscent of America’s antitrust actions against Standard Oil. I return, then, to the archipelago — to the tale of market dominance, where commerce and power have always collided across these waters.

“The same worms that eat me will someday eat you too.” — Viagra Boys

The Cost of the Spice

On Arrakis, the spice flows — but so does the cost. Maybe David Lynch’s coffee addiction fuelled his 176-minute space epic, but its sequel reimagines Wadi Rum and the Abu Dhabi desert so harsh it could make even Zendaya faint.

The Makassar War, too, was seen as unavoidable — though its true cause remains contested. Blamed for igniting conflict through secret letters, Viera’s fate intertwined with Makassar’s fall as Arung Palakka’s alliances closed in. Captives were traded as spoils and sold in urban markets. The VOC’s violent monopoly scattered Sulawesians across the archipelago, forming a diaspora. Contracts on cloves and spices were set at fixed prices, while a pass policy controlled the trade routes.

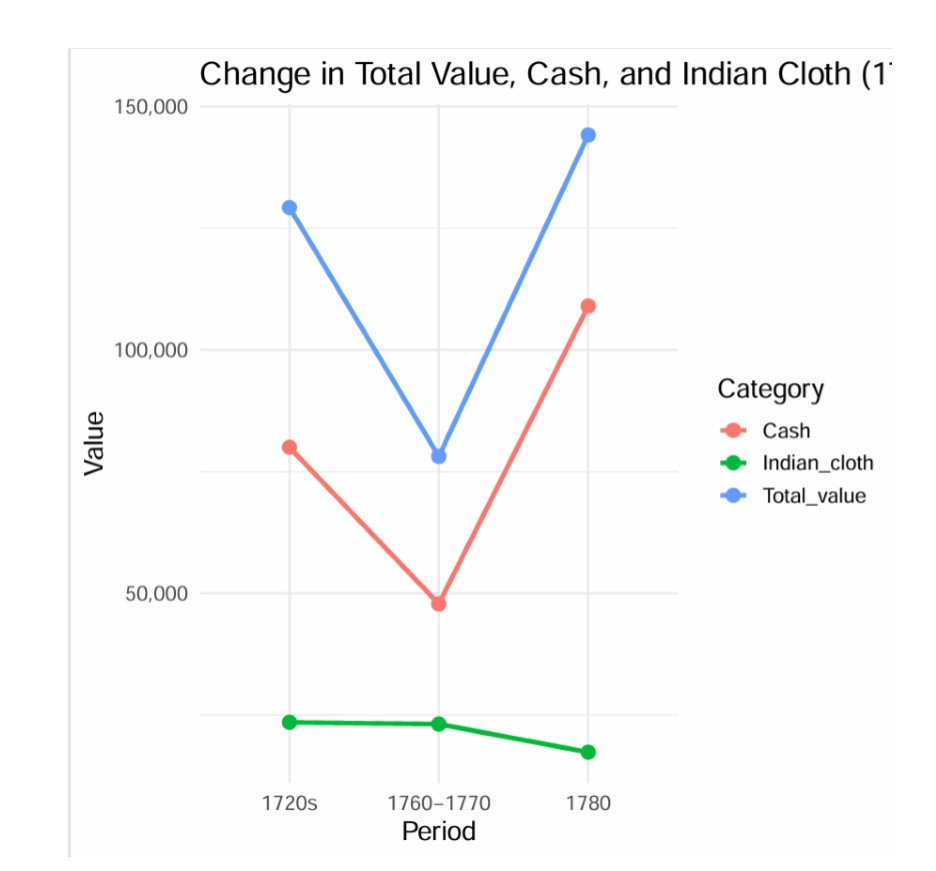

VOC shipping records reveal a sharp decline in trade diversity — a shift from varied goods to greater monetisation. The fall of Makassar left its trade channels dry, a stark reminder on monopoly and often their destructive cost.

CREDITS

- Fumagalli, C., Motta, M. and Calcagno, C. (2018). Exclusionary Practices. Cambridge University Press.

- Scherer, F.M. (1996). Industry Structure, Strategy, and Public Policy. Addison Wesley.

- Hammond, L.D. and Poggio Bracciolini (1963). Travelers in Disguise, Narratives of Eastern Travel by Poggio Bracciolini and Ludovico de Varthema.

- Fernández-Armesto, F. (1996). Millennium.

POST CREDITS RE-BITE

“even better how would you like to have the remaining sake?”

First encounters are often awkward — as Dune audiences might recall from Stilgar and Leto’s brief exchange of bodily fluids. Yet few would assume a collision of societies and peoples would unfold shifting ideals in free trade, autonomy and multiethnic trading networks to disputing European monopolies.

Adam Smith once stated that monopoly is the enemy of management, Schumpeter went on to argue that technological process and hence the rate of growth of output would be rapid under a monopoly than under competition.

The case of crude oil expansion in the United States during the 19th century saw larger refineries constructed with rigorous quality control and tighter cost reductions.

Perhaps the Baron would bathe well in the thought.